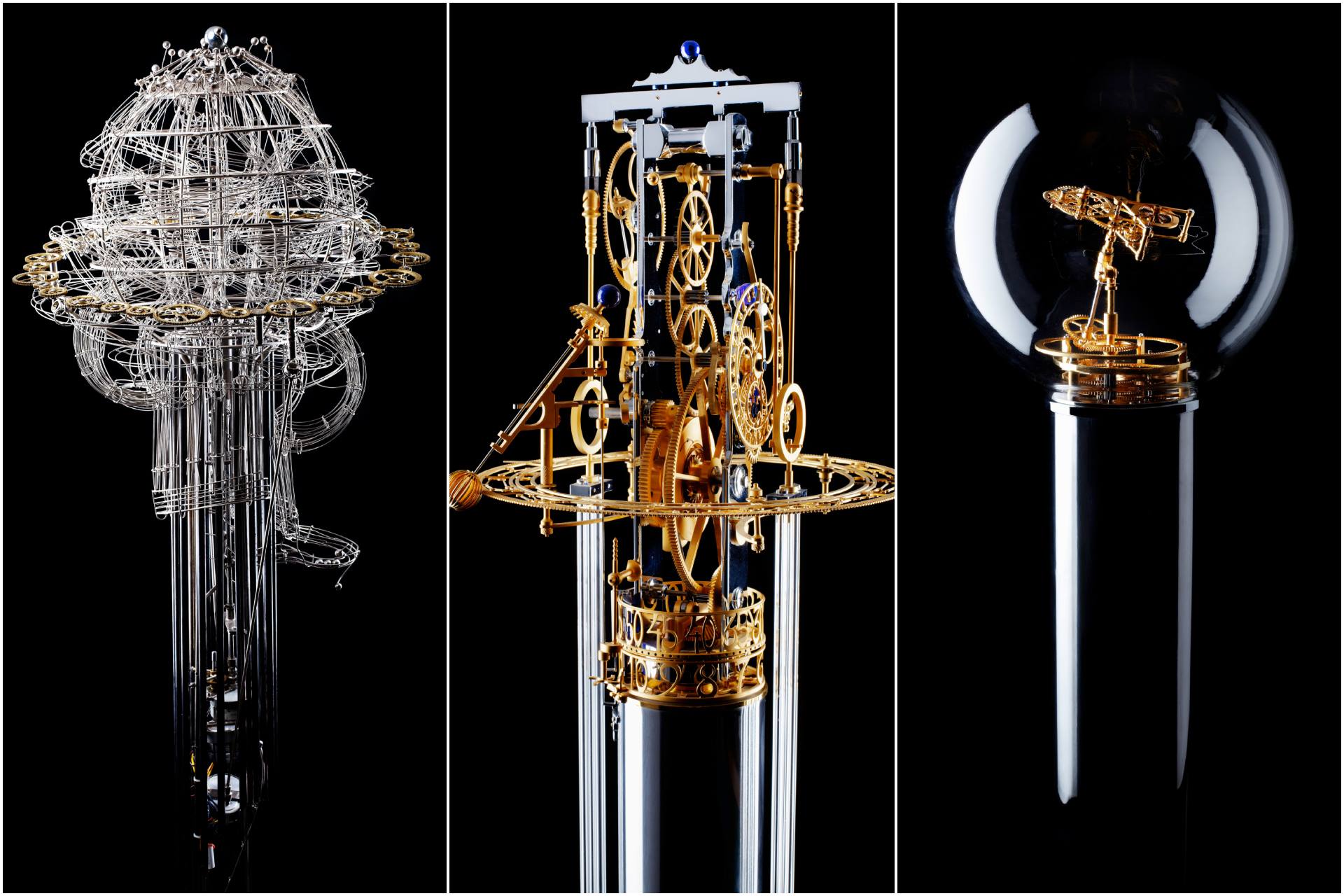

‘Horology is an extremely creative field. I can’t put it in words, but once I start thinking about clocks, my ideas never stop’

Self-taught clockmaker Miki Eleta is a member of the Horological Academy of Independent Creators and his unique mechanical and artistic masterpieces are a result of his deep fascination with timekeeping, innovation and kinetic art

‘For me, the construction of a watch is a playful and fascinating experiment. In order to give a chance for an yet undiscovered element to come to life, I strive to surprise myself without concern for failure. Relentless passing time may be one of the reasons why I produce only unique watches.

Truly, who wouldn’t want to exhaust as many possibilities and uncover as much as possible? I see a watch as much more than a mere timekeeper. Through its form, it can convey some of what I have experienced while creating it. It’s the joy of precise movements, sounds, harmonious shapes, and inexhaustible possibilities in answering a fundamental question: what is a watch, actually?’

The author of these beautiful sentences dedicated to horology is the self-taught watchmaker Miki Eleta, one of the 35 members of the Academy of Independent Watchmakers (ACHI), an artisan, creator, seeker of harmony, dreamer, artist who, in 20 years of creative work, has made around 40 mechanical devices and watches.

Admittedly, referring to his creations as watches might sound somewhat diminishing because they are mechanical and artistic masterpieces crafted by hand on demand, adorning palaces around the world, even the salon of a superyacht (Nobiskrug Artefact o.p.a).

Even though this is a Skype interview and we’re hundreds of miles away from his Zurich workshop, we can almost feel Miki Eleta’s miraculous energy – an energy that’s easy to fall in love with. Despite making some of the most fascinating clocks in the world for select clientele, Miki Eleta is living proof that brilliant people are warm and simple, in this case full of Slavic soul and a Bosnian sense of humour.

YOUR LOVE OF MECHANICS DEVELOPED WHILE YOU ACCOMPANIED YOUR FATHER WHO WORKED AS A TRAIN DRIVER.

I often joined my father on the Sarajevo – Višegrad – Titovo Užice route. I distinctly remember one event that made me fall in love with trains and I always get goosebumps when I tell it. There’s a railway line that crosses Šargan Mountain, the so-called Šargan eight, full of tunnels and bridges, where you can feel the wildness of nature and the power of the mountains. While we were passing this magnificent route, I asked my father if I could drive the train for a while. I was a train driver for 15 minutes and operated that huge machine that pushed its way through the rugged terrain.

The sound of railway lines, the memorable noise of the train, the immense power of the machine winding its way through mountains is something I never forgot. Even now, when I see a steam engine, I want to climb up, pull the lever and travel somewhere. Just like Jack London’s adventures.

YOU WERE BORN IN VIŠEGRAD, BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, AND MOVED TO SWITZERLAND TO FULFIL A DREAM – BUY A FLAMENCO GUITAR.

I have to go back to the past. When I was six, I heard flamenco playing on the radio. I was mesmerized by the sound, the emotion and the love flowing through the wires. As my sister was working in Switzerland, I asked her to send me some money so I could buy a decent guitar, and she asked: ‘Why don’t you come here to earn money and buy yourself a guitar?’ It was an excellent idea. After learning German in Višegrad for a few months, I got a job as a medical technician and bought a guitar from my first pay check.

So, I can say that the guitar guided me in life. Like everything else in my life, I learned the Flamenco autodidactically, there was no one to teach me. Later on, I was taught by Andalusian Roma people in Seville. The music their fingers produce is God’s work.

WHEN DID YOUR LOVE OF CLOCKS START?

When I look back at my life, it’s all about details. The train, the guitar and kinetic art. I worked all kinds of jobs in Switzerland – from football coach to musician and in 1996 a friend asked me to make a so-called muster board to demonstrate his clients gold, silver, titanium… I told him I would make a machine to demonstrate it and that’s when my kinetic art was created. It was a huge success. By 2000 I had made more than 80 pieces and then one detail directed me towards clocks.

One time my creation called Chaos was on display at an exhibition and a young man I never saw again after that asked me to explain to him how the thing worked. After my explanation, he just replied: ‘You can’t make precise things. That’s why this one is chaos.’ I replied: ‘You evidently didn’t understand my elaboration, but come back next year and I’ll make a clock to show that I can make precise things.’ And so, I decided to make clocks when I turned 50. I started visiting clockmakers and learning…

Choosing a path that is very typical of me. My unique timepieces take six to ten months to make. You need to be bold and different, as people in Bosnia would say, you have to be a bit ‘cuckoo’. I sometimes refused a lot of money to make a few clocks that are identical, but money doesn’t matter much to me anyway. I didn’t have any in Višegrad, and here in Switzerland I have enough for a decent life and for my tools, which have to be top tier. Each new idea at my workshop brings me much more joy than money. When I take a piece of brass and start making a new clock, one gear train at a time – it’s like a steam engine journey, you enjoy it and you’re in no rush to get anywhere.

Miki Eleta avoids computers and designs clocks by hand instead, using his own designs and sketches made on paper. He has never owned a car and there are no machines in his workshop because he cuts each gear train himself. The clocks carry his emotion and signature and each new timepiece he finishes fits the mosaic of the story perfectly. He’s a clockmaking romantic and his creations are a labour of love.

‘The world of clocks is fascinating and endless. People have been measuring time for millennia. Just look at the ancient Antikythera mechanism. Horology is an extremely creative field. I can’t put it in words, but once I start thinking about clocks, my ideas never stop. It’s an artistic fervour that I’m completely overcome with when I create. Bear in mind that I don’t know what time is, I don’t believe anyone can explain it with 100% certainty. What we call time is our human agreement that a day is 24 hours. The only thing I know is that life is very short and we have to use it as best we can. The older and wiser we get, the more we appreciate every minute of time we were given.’