The art of dry-stone walling being inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list is a homage to generations of unknown builders from coasts around the Mediterranean

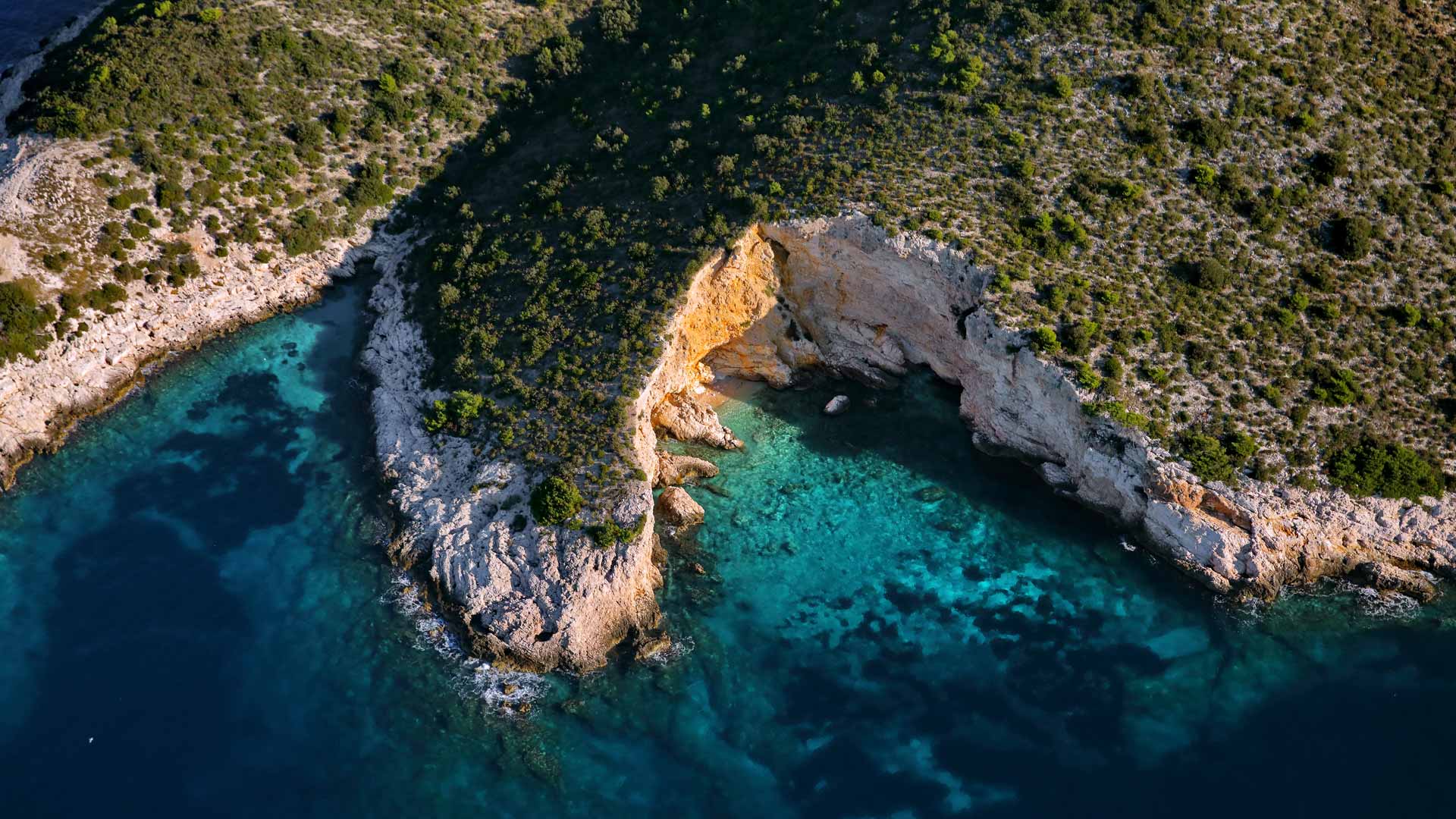

Legend has it that the Adriatic islands were created by gods who decided to play with excess rocks by dumping them into the sea because they didn’t know what else to do with them, but they were so beautifully arranged that they decided to leave them there forever.

When humans began inhabiting these rocky shores, they might have been following a divine example, for having nothing but stone and a will to survive, they took stones and built an impressive net of drywall and objects, from megalithic prehistoric forts, to small shelters in the field – trimovi and bunje – to modest housing facilities and entire settlements, which were created from nothing – dry, without mortar.

A legendary island journalist, who shall remain nameless, may he rest in peace, was one of the first who took clueless tourists on tours along the coast, and when they kept asking who built these vast rows of drywall stretching from the sea to mountain tops, the clever seaman had a brilliant answer – aliens! And for a moment the enlightened tourists would remain silent because, honestly, who would be so crazy to take the limestone from the land, cut it into shapes and build houses, fence enormous karst fields full of rocks lying there for millennia, waiting to be formed into something.

The mentality was created in the same way; laboriously reflecting man in nature, and the stone structures created purely out of necessity, have become emblematic, as a strong means of connecting and grasping the identity of local communities, which is why they were listed as Croatia’s intangible cultural heritage. If you meander the sea through the Kornati, you can’t help but notice the kilometres of single drywalls, small fishing houses and fenced oases of fertile soil with few olive trees that have taken root in the arid ground.

The Kornati and the area surrounding it, whose inhabitants have lived off of Kornati, but also on it, are the place where you will find some of the timekeepers of this tradition that has begun to slowly disappear.

The Latin Sail Regatta and all that goes with it have strengthened the will and force of the ‘Kurnatari’, the same will that enabled them to endure hours of sailing or riding to remote locations, and the local cultural identity got the stimulus for a new stroke and new generations of tradition bearers.

In fact, there is no island in the Adriatic without a monument to human aspiration to hide from the storm, scoop up water, or fence off a piece of land to survive, and all that by letting stone slide through their fingers. This correlation of man, animal and nature, in the desire of a modest worker to overcome the conditions above and under his feet, created a modest, but genuinely intuitive and unique and unmatched architecture for every island, every village, or mountain, and often, I dare say, real art, because it was built by people without any formal knowledge, yet genius in their thinking about the environment and functionality.

Looking at these rocky hills from the air, there is rarely a slope, especially on the islands, which has not been cultivated using drywall, and the natural slope turned into a horizontal piece of land is sufficient for growing vines, olives and all the fruit of the Mediterranean.

Therefore, the art of dry-stone walling being inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list is the ultimate homage to generations of unknown builders from coasts around the Mediterranean, who have left behind an incredible heritage, which has, thanks to associations, individuals and organizations, managed to stand the test of time and the aspirations of the modern man.

Urban culture has taken root in traditional architecture, sometimes changing it beyond recognition, but the constructive expression derived from the need to keep life in harmony with the arid landscape, is visible even in the smallest wall or stone terrace that overlooks vast stretches of vines, guards olives from the wind or keeps precious water in stone cisterns.

This genius simplicity is the key to deciphering the formula for survival. A long time ago, man began straightening natural curves and putting them in more comprehensible forms and has spent centuries perfecting the art and his relationship with stone. The walls of Dubrovnik, Trogir or Pula, numerous palaces and hidden courtyards within towns, all of them are puzzle blocks that were shaped by thousands of blows by local masters, shaping them into right angles, squares and rectangles, to mark their existence and leave an almost everlasting trace in stone.

There is no better place than Korčula and the small rocky islands in front of the town – Vrnik or Kamenjak, to witness this relationship between man and nature. Shaped by stones, they have been meeting the people’s need to build their houses and imprint memories and traditions into stones for centuries. Thanks to this geomorphologic advantage – the abundance of stones and man’s ability to manage natural resources, especially water, settlements began to crop up, and then the towns throughout the Adriatic and its hinterlands followed.

That’s why I like the phrase the architecture of survival, because this is precisely what traditional construction is; an architecture managed by economic activity, (self-) sustainable in every respect, in a complete eco-friendly harmony, with no deficit for the Earth. This standard is virtually unattainable nowadays. Customs as an identity-related phenomenon, and also the media of national culture – frozen experience and knowledge of ancestors passed down over centuries, which not only shaped space, but also ourselves.

Around here, people have learned how to live with stone, from the stone, and sometimes for the stone, but often if we look, we do not hear or feel the stone. The stone talks, or better yet, it sings, and these are not mythical stories, ask any stonecutter, whose hands shaped tons of blocks and created numerous delicacies, whether the stone actually sings. You will not be surprised by the answer itself, but you will hear a completely new language that is sometimes used to talk to stone, which is the language of intuition.

That voice is sometimes transmitted to the taste hidden in olive oil for which there is no organoleptic unit; the palate feels it because without it plavac mali would not be tart, and Pošip would not be as golden, so it is no surprise that the voice of the drywall has only recently been given a modest place on labels and brochures. It is that major thirst or taste, the bouquet that everyone talks about, and it is in fact the taste of limestone and drywall. Terroir, the experts say, is the secret formula of top-quality wines and there is no better evidence for it than Pelješac.

It is home to one of the most emblematic plavac mali varieties in Pelješac and it comes from an extensive drywall area around Ponikve, where this variety, passing through a thin layer of soil, takes root deep in the limestone and draws from it what it needs the most; adding vigour and character or, if you insist, bouquet, to grapes.

And that is precisely what makes the essence of coexistence between a Dalmatian and the rocky landscape, his desire and intuition that led him to realize that nature should not be exploited senselessly, but that he should offer it something sincere, shaping it in accordance with tradition, and it would surely return the favour, be it in the form of the taste of a glass of wine or a drop of olive oil.

Text Filip Bubalo

Photos I. Pervan, M. Jelavić, D. Peroš, M. Romulić & D. Pačić