- Latest articles

- Popular articles

- Latest articles

- Popular articles

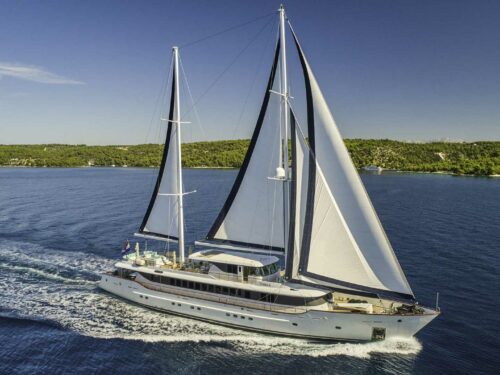

Yacht Charter Croatia

Find Your Perfect Yacht

- luxury YACHTS

- LUXURY SAILING YACHTS

- Motor Boats

- CATAMARANS

- SAILING BOATS

Yachts Croatia

Yacht Charter Croatia

Find Your Perfect Yacht

- luxury YACHTS

- Motor boats

Free Newsletter

Subscribe now to receive exclusive content,

news and special offers

news and special offers

Free Newsletter

Subscribe now to receive exclusive content, news and special offers

yachts.croatia

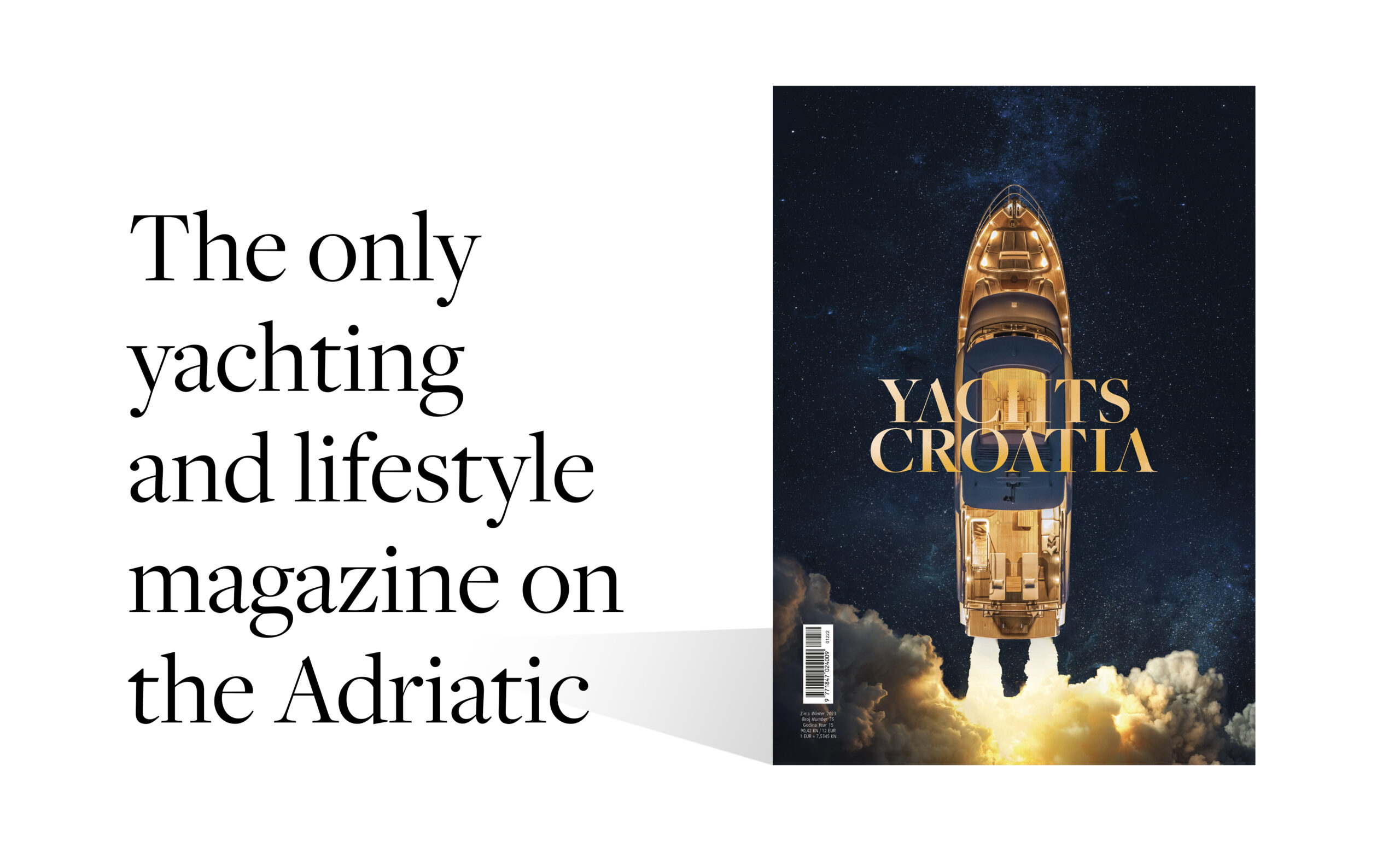

Let us open your eyes to Croatia!

Follow #YachtsCroatiaMagazine and find the magazine on the nearest newsstand!

Let us open your eyes to Croatia!

Follow #YachtsCroatiaMagazine and find the magazine on the nearest newsstand!

yachts.croatia

Let us open your eyes to Croatia!

Follow #YachtsCroatiaMagazine and find the magazine on the nearest newsstand!

Let us open your eyes to Croatia!

Follow #YachtsCroatiaMagazine and find the magazine on the nearest newsstand!