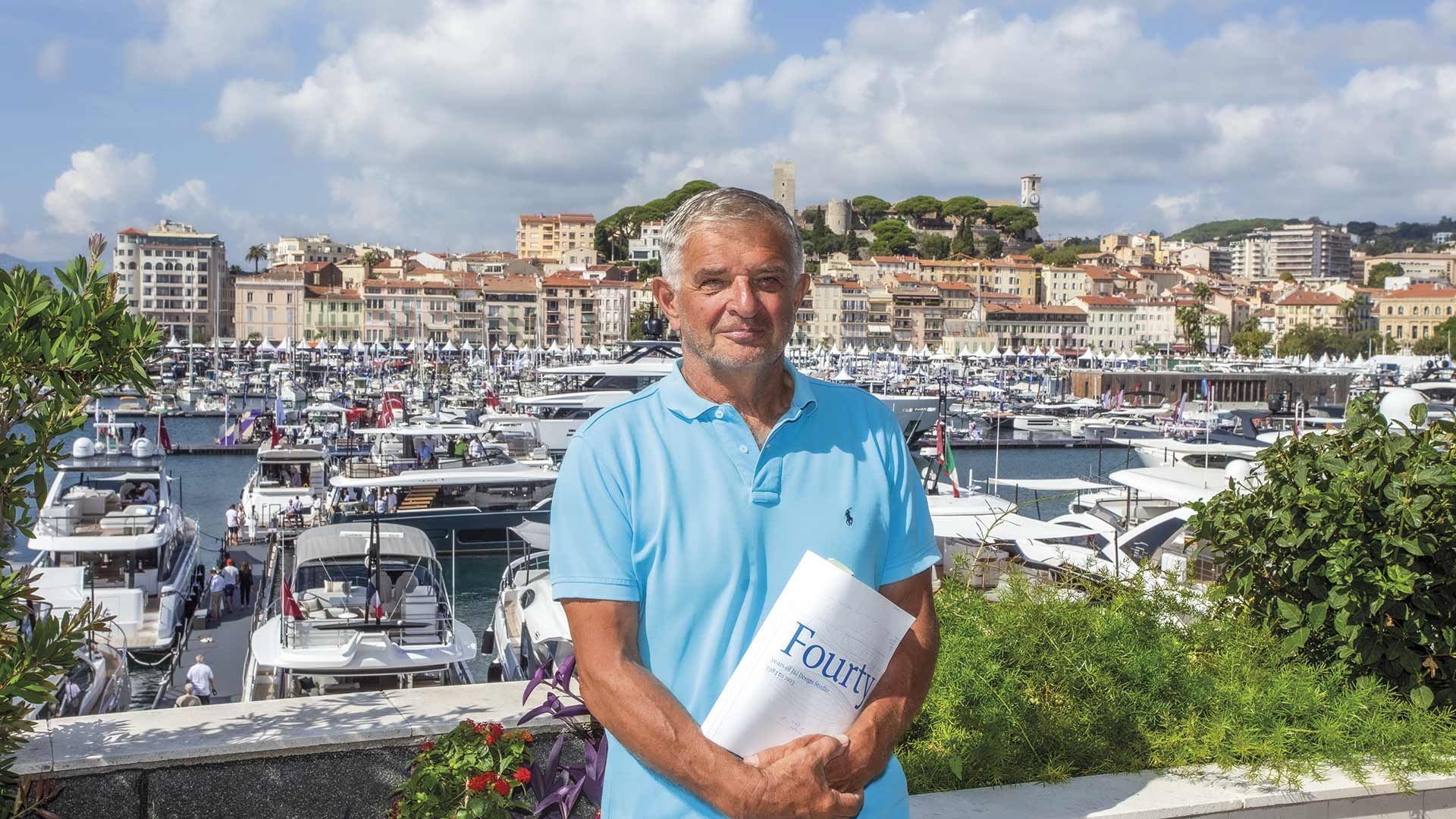

The book about the forty years of activity of the Jakopin brothers and their company reads like an encyclopedia of nautical history, with unique records about their projects, as well as individuals who propelled forward the nautical industry. In addition to its factual significance, the book can also be viewed as a synthesis of the know-how that the two Slovenian designers have acquired over the years, and selflessly share with readers

Four decades have passed since the brothers Japec and Jernej Jakopin, through their studio J&J, launched their first project to the nautical world. To celebrate this milestone, the brothers have published brimming with incredibly interesting tidbits from the history of the nautical industry, painting a detailed picture of the passion our neighbors cherish, and which motivates them in their daily lives on the northern slopes of the Julian Alps.

In those four decades, the brothers have designed close to 400 projects, that were embodied into more than 70,000 pleasure vessels, and have won 119 international awards – almost three awards each year. They also tried their hand at the world of boatbuilding, but naval design and development have always been and remain today their strongest assets. We have used their birthday as an excuse to interview Japec Jakopin, who told us everything we wanted to know about the book and shared his wisdom and everything he’s learned on his way to the top of the nautical industry.

Japec loves everything nautical so much he could talk about for days, so if you feel the same, don’t miss his book. The story of the brothers Jakopin began in Yugoslavia, at a time when European nautical was experiencing a great boom. Japec believes that they were in the right place at the right time, so he’s quite modest when talking about the beginning of it a…

‘We didn’t know it then, but when you look back, it’s clear that if all the right elements hadn’t been present at that moment, nothing would have come out of it, we wouldn’t have created anything. But the Adriatic came to life, and Elan were the only ones capable of creating technologically advanced boats. I dropped out of med school, and the rest is history…’

YOUR BOOK COVERS ALL THE FOUR DECADES OF YOUR ACTIVITY. WHAT WOULD YOU SAY IS THE MOST SIGNIFICANT PART OF THAT PERIOD?

My favorite is the first part of the book, called ‘Story’, showing the timeline of our journey – a journey through time and through the nautical history of both Slovenia and Europe, possibly even the world. We have collaborated with sixty shipyards from all over the world, but I never see them as companies, only people. We have learned something from everyone we have worked with, and that’s the real meaning of our journey. We’ve worked with some truly creative people, and have learned a lot. Meeting and getting to know all of them was the most significant achievement in these 40 years, which is why in the first part of the book we have introduced many of them, through short anecdotes that paint vivid pictures. Many of them have sadly passed on, and we wanted them to be remembered, as they were experts, geniuses, nautical legends.

WHAT WAS THE MOST IMPORTANT LESSON YOU HAVE LEARNED?

Definitely the impetus to pass on knowledge. Nautical industrial design is composed of many disciplines. As far as naval architecture, we have learned the most from Doug Peterson, the designer of three America’s Cup winners, who was very fond of us and has visited us in Slovenia many, many times. We were surprised by his attitude, because just like all the great ones, he was ready to share his knowledge with anyone interested, he was delighted to be asked for advice. The truly great ones will always tell you everything you want to know, they have no secrets. Once we asked Doug how much bigger his know-how was than ours, and he answered jokingly that he knew about twenty-five million dollars more – because he had spent that much on water tank tests, something we still hadn’t tried. When we worked on the Made in Slovenia sailboat project, we started a little competition between three bureaus: Doug Peterson, us and Guillaume Verdier, who was a young designer at the time, barely older than a kid. The project was 30 meters in length, and at that time Verdier was relatively unknown, he stuck to Doug to learn from him. Two years later, Guillaume Verdier’s designs won four out of five top spots at the Vendee Globe. I called him to congratulate him, and he said: ‘Doug taught me everything. His knowledge did not die with him!’ I am glad to have been there, to have witnessed this – especially since it helped us get Verdier to work with us on the BMW foil project. He accepted without hesitation, putting everything else aside for the moment. We have a good, friendly relationship with everyone we mention in the book, and that is something beautiful.

WHAT WERE SOME OTHER IMPORTANT STEPS ON YOUR JOURNEY?

Our relationships with shipbuilders. I worked for Jeanneau from 1988 to 1990, and then continued to collaborate with them after Beneteau bought Jeanneau. At that time, I argued every day with Jean Francois de Premorel, who was a hotheaded Breton, very similar in character to me. We were working on project Lagoon and carbon catamarans. That’s why he ended up missing three fingers, because he was constantly cutting something. He also constantly criticized our new designs, and in many instances, he was right. Many year later, I got a call from Bruno Cathelinais, then former CEO of Beneteau, who helped developed it (his right hand was Dieter Gust, the founder of CNB), who invited us to a meeting. When Jernej and I showed up, there was Jean Francois, waiting for us, and I immediately said we wouldn’t be able to do much together, because we would argue without end. Then Mr. Cathelinais corrected, saying it was Premorel himself who insisted we came. Such relationships that were intimate and direct were one of the basis of our work, and we had them with many companies we cooperated with. We’ve always aspired to be surrounded by people who know more than us, because that allowed us to learn by osmosis, you’re going to learn something from them even if you’re the biggest fool in the room – that’s how you learn. If you’re always the smartest, you’re not going to improve.

WHAT HAS CHANGED IN THOSE FOUR DECADES?

We used to work with founders and owners of shipyards who did everything to succeed. Today, many owners are business entities, funds that think of nothing but the profit, and if a company fails, their CEO will just log into LinkedIn and search for another spot. Back then, you could call someone for help; say, if there was a problem with Harken, you would call Peter Harken, and if some piece of equipment was wrong, he would fix it within a week. If they had a problem with the mast, they would call one of the Hall brothers. If we noticed the CEO was making all the wrong moves, we want to talk to the owner, which is hardly possible today. Many companies today do not have a compass, they’re like airplanes flying through the fog on autopilot. Unfortunately, that’s the biggest difference between then and now.

HOW MUCH OF YOUR BOOK IS DEDICATED TO PROJECT GREENLINE?

Greenline was an excellent project that we designed for Beneteau in 2008. I was very proud to travel to Paris with a wonderful PowerPoint presentation in French, to presented the project to Annette Roux, one of the building blocks of Beneteau. I was delighted at the event. And then at the end, she asked me if it was a hybrid drive, I said yes and she kicked me out. Later we found out that they made the Lagoon 420, forty units with hybrid drive, which failed and cost them millions of euros. I was devastated, but our other French partners suggested to build the project ourselves, seeing how much we believed in it. That’s how Greenline was born, to prove to everyone how great it was. Every project has its story, that’s what this book is all about.

WHAT’S THE STORY OF SHIPMAN?

We had a co-owner, Seaway, a financial institution, and they insisted that we build ships, but we wanted to stick to development. We didn’t want to compete with our studio’s clients. We were sitting at a bar in Ljubljana; Doug Peterson, Bill Green, who made carbon gliders, and Giovanni Belgrano, the owner of SP Systems, who invented the Sprint technology. He suggested that we build carbon sailboats, as they’re made in small series, but we would still appear to be building something. Plus, it could be fun. After a few more beers, he promised he’d let us use his technology, and Bill Green promised to educate us in building carbon sailboats, as they were just finishing Prada 2. And so it was; his son and daughter led a team of six people who taught us about carbon technology, and so Shipman was born.

IN THE 40 YEARS OF ACTIVITY, IT CAN’T HAVE ALL BEEN LUCKY COINCIDENCES AND SERENDIPITY. WHAT DO YOU CONSIDER PIVOTAL FOR YOUR SUCCESS?

Our curiosity and our passion the sea and all things nautical. I’m fascinated by boats, by the sea, which why I’m also a diver. Also, because I ruined my knees climbing mountains and skiing. I can now reach 87 meters in one breath, and my goal is to reach 100 meters. Thirteen to go.

HOW DID YOU SELECT THE PROJECTS YOU TALK ABOUT IN YOUR BOOK, YOU COULDN’T DISCUSS ALL 400 OF THEM?

It’s like asking a mother which child is her favorite. All those 400 projects are our children, so it was difficult to select the most important ones, but some of them were closer to my heart. The first among them was Elan 31. We have never sailed so much with any boat and had so many sleepless nightshts. I am also very fond of three Jeanneau sailboats, our projects for Sunbeam, and our projects Shipman, Greenline, Skagen.

THE BOOK MENTIONS THE FUTURE OF YOUR COMPANY. WHAT ARE YOUR PLANS?

My intimate wish is for our studio to go on. The history of this industry shows that most studios don’t survive the change of generations. From the very beginning, we wanted to have a convincing and solid team; we have eight nationalities working together, we just want us to be s family. I have great hope that young people will have the energy, creativity and ability to lead our business. Nothing lasts forever and we don’t know what the future holds for us, that’s why in the book we quot Heraclitus: the way up and the way down are the same way. We’ve been lucky for the last 40 years, and I hope it stays that way. Jernej and I are always asked when we will retire – but for us, this is a job and a hobby, so we answer how can one retire from a hobby?

Photos Mlađan Marušić, Jure Korenc & Nicolas Claris